‘Better Than Before,’ by Gretchen Rubin is reviewed in the NYTimes by Hanna Rosin today. The book is a ‘street science’ explanation of how habits can structure our lives, and how we can change our habits to live more the way we want to live.

For a few months, Gretchen Rubin’s first book, the longstanding best seller “The Happiness Project,” perched on my bathroom radiator, its cartoonish yellow font in conversation with a stray rubber ducky. I read it in small doses, convinced with each sitting that I could go to sleep earlier, or discover a hobby, or make three new friends. I often forgot the specific advice shortly after reading it, but the sight of the little bluebird on the cover floating across the perpetually cloudless sky was frequently enough to give me a lift.

“The Happiness Project” lays out life’s essential goals — “Boost Energy,” “Remember Love,” “Contemplate the Heavens.” Her new book, “Better Than Before: Mastering the Habits of Our Everyday Lives,” serves as a kind of detailed instruction manual on how to achieve them. Rubin was inspired to write it after a friend reported to her that she wanted to go running more but couldn’t get started, even though in high school she’d run track and never missed a practice. Another kind of person might be content to ease the friend’s guilt with some sisterly empathy: Who at our age has time for a daily run?

But anyone familiar with Rubin’s constantly updated blog knows that’s not how her mind works. Faced with the fog of human stubbornness, she briskly turns on her mental wipers. As Rubin reports, nothing in her happiness research explained her friend’s predicament, so she began cogitating until: “It was obvious! Habits.”

Habits “are the invisible architecture of daily life,” she begins. “If we change our habits, we change our lives.” She then proceeds with her trademark bullet points and breezy anecdotes to address various vexing questions, chief among them: “Why is it that sometimes, though we’re very anxious — even desperate — to change a habit, we can’t?” and “Why do some people dread and resist habits, while others adopt them eagerly?”

To get another important question out of the way: Why do we need another book about habits when Charles Duhigg’s “The Power of Habit” has been on the best-seller list for over three years? I’m not sure, but at least the books are very different. Duhigg’s book travels through neuroscience labs and corporate America, following unexpected characters, turning up surprising discoveries. Rubin, too, reports doing extensive reading on behavioral economics, animal training and the design of kindergarten rooms, among other intriguing topics. But she shares little of what she found, perhaps because that sort of intellectual adventure is not what she’s after.

Instead, she describes herself as a “street scientist” whose aim is “to see what’s in plain sight.” For her examples, Rubin doesn’t stray far beyond the neighborhood. Her guinea pigs are the characters familiar from the last book: her husband, Jamie; her daughters, Eliza and Eleanor; her diabetic sister, Elizabeth; and a few unnamed friends. Her daughter wants to stop buying candy on her way home from school, her friend wants to clear out some junk in his apartment so he can get down to writing his screenplay, Rubin herself wants to email every day with her sister. When dispensing advice, she is fearless about using clichés — “The most important step is the first step” or “Don’t get it perfect, get it going.”

Once when I was a young reporter, I covered a conference headlined by the motivational speaker Zig Ziglar. He was a salesman and a Christian, and his speeches led up to something like an altar call. One had the feeling listening to him that transformation was arduous work. He spoke so loudly and insistently that I could no longer hear the voice in my own head. To emerge better than before, I had the impression I’d have to first be stripped to nothing, and then born again.

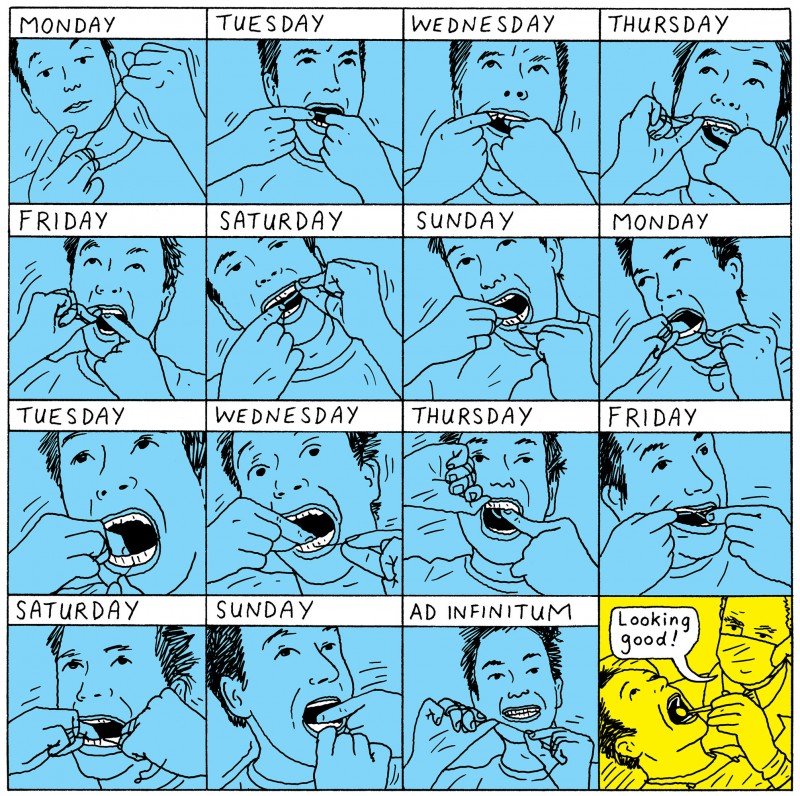

Rubin, by contrast, only asks us to tinker at the edges. The genre she’s mastered could be called secular self-help lite. The problems are familiar and undaunting, the goals are eminently attainable, and the core remains unchanged. Tricks on getting yourself to go regularly to the gym, say, come up in nearly every chapter. (For example, “the Strategy of Pairing” — watch your favorite TV shows only while you’re on the treadmill.) No desired daily ritual is beneath her notice. One reader writes to her blog: “I dreaded my dentist appointment because I knew they’d ask how often I floss. It occurred to me that I could just floss every day, and then that question would never bother me.”

Rubin’s central insight in the book is that different people will respond differently to habit-forming strategies. She divides people into four types, depending on how they respond to expectations. On one end of the spectrum are upholders, who eagerly meet their own and other people’s expectations. On the other are rebels, who resist. (Most of us fall somewhere in the middle, with the questioners and the obligers.) With each of these types come further classifications: Are you a lark or an owl? An underbuyer or an overbuyer?

The lists give the impression that Rubin is open to a great diverse and varied world of types, from Tracy Flick to Che Guevara, from the Dalai Lama to Oprah. But in fact the variety affects only what process works best for them. Once they submit to habit, the improved specimens narrow, demographically, into one type: the type that eats fewer doughnuts and more vegetables, exercises regularly, sleeps more, procrastinates less, organizes bookshelves, engages deeply in relationships and generally lives in a cozy world in which a big problem is whether the dentist will be mad at them.

My favorite passage in the book is a reprinting of Johnny Cash’s to-do list: “Not smoke. Kiss June. Not kiss anyone else. Cough. Pee. Eat. Not eat too much. Worry. Go see Mama. Practice piano.” I like the list because it contains the seeds of its own undoing. Habits have an eternal appeal because they remove the element of choice. They hold out the promise that in the future we can improve ourselves almost automatically just by moving through our days, like the evolved operating system in the Spike Jonze movie “Her.” But Johnny Cash understands that temptation is not a virus we can remove. His list isn’t linear, it’s circular. He will never turn into June. He will always be Johnny, and every day he will cough, pee and eat. Just as every day he will have to resist the urge to kiss someone else.

As it happens, when I was reading this book I really needed it. My husband was away more than usual, and my days felt more empty and formless. One Monday morning I decided that all week long I would earnestly submit to habit. I wrote first thing for two hours each morning and stayed off the Internet. At 11 a.m. I made myself tea (that’s called a cue!) and checked my email. After sticking to the routine for three days, I arranged to see a friend for coffee (a treat!).

By the end of the week I was feeling calm and productive, in perfect harmony with the cosmic schedule. Then on Friday evening the cat knocked “The Happiness Project” off the radiator, revealing the book underneath. It was a collection of Dorothy Parker poems, and here, I swear, is the poem it opened to:

Her mind lives tidily, apart

From cold and noise and pain,

And bolts the door against her heart,

Out wailing in the rain.

What was it I was supposed to do again?